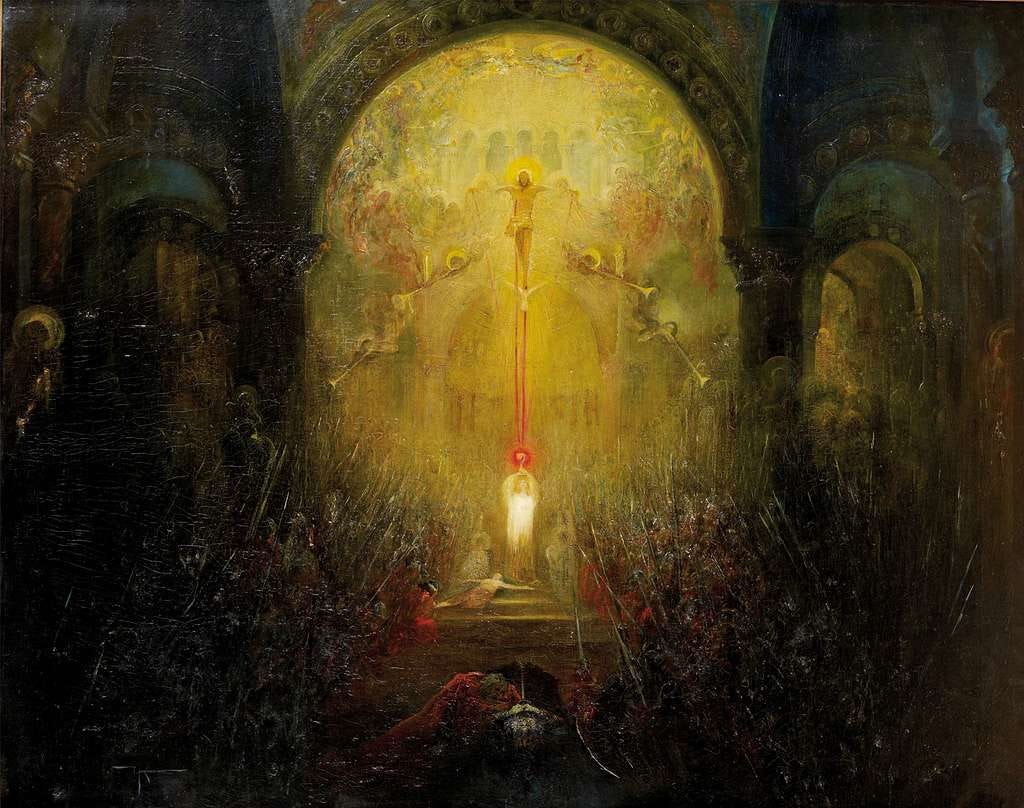

When the familiar footholds are gone

And life scattered into all the little pieces,

The Great Gatherer comes

To collect all the fragments together like shoal from the shore.

Slowly she unwinds and unravels each piece,

Back to its core,

Until it lies like molten gold in her palm.

Then, threading each piece with her silent needle,

She weaves each with the other back into a whole-

And all that is worthy holds its form,

Silently holding me in the deepening dusk.

When we were still at the farm in Cornwall being buffeted around by the keen wild winds of the west, we hunkered down in the evenings to watch the Hobbit Trilogy with our newly-made friends. After lighting the log fire and eating too many biscuits, we followed Bilbo on his many adventures with the dwarves. It reminded me of several things to do with the nature of travelling. Firstly, that to adventure means to leave something behind: a place, a way of life, a group of people, a mindset, a home.

Secondly, adventure and travel often involve a returning of some kind; sometimes to the same place, the same way of life, the same people, the same mindset, the same home, where you discover yourself recalibrated, reorientated through the experience. T.S Elliot put it like this:

"And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

Leaving things behind can be liberating. It’s like suddenly discovering you’ve grown a pair of impressive feathery wings- off you soar, into a sky of dreams. But flying into the unknown can also be a death experience, where all that is familiar and safe falls away with frightening speed and you are left hanging in the void wondering what on earth you are doing so far from home and how to the devil to get back down.

The sky of dreams can contain all sorts of things you could never have anticipated. I am sure Bilbo didn’t envisage being trussed up like a chicken by the trolls, about to become a tasty hobbit kebab. If he had, maybe he wouldn’t have left the Shire.

So far we haven’t met any trolls. But I think we may have found our Rivendell. Along our road of adventure, we have stumbled across a hidden gem. Tucked into the Wye Valley in South Wales, Ty Mawr Convent, the Society of the Sacred Cross, stands as it has done for the past hundred years. The Society, a community of nuns who live, pray and work together daily in a life of contemplation, was founded in December 1914. Ty Mawr, meaning ‘Big House’, did not become the community’s home until 1923, when it was bought, at a considerably reduced priced, from a ‘Mrs Hankey’.

Since then, a dedicated community has lived here in a continuous rhythm of prayer. The main house, a handsome, three-story stone building, stands in sixty five acres of land. A lush patchwork of wildflower meadows, orchard, woodland and wetland, it also contains a bounteous kitchen garden which helps supply and sustain the kitchen menu. Mealtimes are silent, apart from Sunday lunch. Quiet pads the flagstone corridors and lobby like snow. Initially, it is a strange and disquieting experience to step in to a place of silence. The noise of the world, and the human mind, comes into focus through sharp contrast to the stillness here.

While we live and work at Ty Mawr, our days are built around the five daily prayer services, peppered with Latin names such as the nine a.m. ‘Terce’ (referring to the third hour of the day after dawn) and the last service of the day ‘Compline (‘to complete’). For the first two weeks, we have spent most of the services frantically fumbling around the Book of Common Prayer and the many different paper appendages that accompany it. One particular nun takes pity on us, dutifully writing out our page numbers and shooting little whispered instructions around her voluminous habit.

To me, the services seem to be a physical enactment, through symbolism, ritual, music and poetry, of a deep Reality within which the Sisters live. The Silence is a way of entering into the awareness of Christ in the soul, God in the world, the great Being Beyond; the services are anchors throughout the day to this reality. Signs, symbols and sacraments are portals to connect to the Divine, not to be mistaken for the Divine itself. But perhaps the less I say the better. One thing silence teaches me is awareness of the cacophony of opinions and judgements elbowing each other for space in my mind. Since I just accidentally sang ‘Jesus the destroyer of faith’ rather than ‘Jesus the restorer’ during the evening service, I am not sure I can be trusted to paint the most accurate portrayal of the life of prayer.

When we are not attending services, we work in the garden- to varying degrees. For example, I do things like ‘gentle weeding’, which generally involves sprawling by a vegetable bed surrounded by a medley of foxgloves and comfrey and poppies, pulling out bindweed. Meanwhile, my husband gallivants around the grounds with the gardener, strimming hedges and chopping down trees. Said gardener is his beard rival and fellow tree-lover, and sports an impressive crop of wiry grey hair. Volunteers from the local wildlife trust come here to work on the land, whilst different people who are involved with the community to varying degrees pass through the Convent’s doors each week. Guests also come to stay here for retreats, for quiet and rest and to enjoy the beauty of this place, and the food. There is a lot of cake, a daily enticement which I cover in my ‘Lead us not into temptation’ part of the Lord’s Prayer, but it doesn’t seem to be working.

Being pregnant is rather enjoyable. I get quite a lot of attention, and people speak kindly to me and periodically pat my tummy. It’s a bit like being a dog, although perhaps a bit more dignified. The only downside is having to traverse the Raging Sea of Hormones: one day, I am sailing along serenely; the next I am battling the Wild Winds of Ineptitude or sinking in the Bay of Catastrophic Thought. On the whole though, I really can’t complain.

Time has flown by, and we have already been here for two and a half weeks. After Ty Mawr, we will be moving to Yorkshire with my Mum and Dad before the baby is born, and for the first six months afterwards. Our journeying will, in this sense, come to an end. Returning, though, might be even more important than setting off. Returning gives pause for thought: for what has been learnt, who we have encountered, what has been lost, and found, for what matters and what doesn’t, for what hinders and what helps.

The physical act of travelling reflects the soul’s search for home. We often return to a physical place, but the journey can teach us to recognise a reality that goes beyond the world as see it now, beyond space and time. I think journeying can help in the discovery of this reality, because, embedded deep into this beautiful, discombobulating life, there is always something worthy to be found.